Querida América

Willy Chavarria and the Echoes of Latinx Feeling

After a winter hiatus, this newsletter is finally back! This week, I’m sharing a conference paper I presented at Pop Con, an academic conference on pop music and fashion. I’ll be back next week and for many weeks after that with more. In the meantime, happy reading!

Much love,

Aneliza

This past fall, Chicano fashion designer, Willy Chavarria debuted his 2025 Spring/Summer Collection, titled América at New York Fashion Week. Set in a vacant warehouse, embellished only with a large American Flag, the show began with Mexican-American family band: Yahritza y Su Essencia performing the song “Querida.” “Querida,” which translates to “dear one” or “darling” is a song directed at a lost lover where the singer asks for their sadness, loneliness, and suffering to be acknowledged. In the opening verse, the singer addresses their love directly, confessing that every moment of their life is spent thinking about their lover. “Mira mi Soledad,” – Look at my loneliness, the singer repeats twice before bluntly admitting that nothing feels right or good without their love. The verse ends with a simple and desperate plea: come back.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Chavarria explained that he envisioned this opening scene prior to drafting any of the designs in his collection. He described “Querida” as a metaphor for the country, saying “The United States is a place people dream of as a land of opportunity and perfection, but once you’re here, you realize we’re actually just yearning for the promise of that.” Such mournful yearning is reflected not only in the soulful belts of Yahritza, but most strikingly in the lyrics that are repeated throughout the song. The performance concludes with Yahritza repeating “Para Cuando, dime” “Tell me when” six times – creating a kind of sonic and affective echo where the listener is moved to reflect on the loss, longing, and expectations expressed by the working class to a silent and withholding America.

In my time today, I take up this notion of an emotional echo and follow it through the designs of Willy Chavarria’s collection. Specifically, I focus on the way Pachuco or Zoot Suit aesthetics are referenced in his collection, and suggest that like the Black and Brown youth who first popularized this style, Chavarria is seeking to make claims about Latinx labor, desire, and belonging in the United States.

Before turning to specific looks in Chavarria’s collection, allow me to contextualize the Pachuco figure his designs invoke. The Pachuco emerged in the 1940’s in the east side of Los Angeles, in the wake of the Depression. As historian George Sanchez explains in his text, Becoming Mexican American, the Depression era was especially cruel to Mexicans in LA not only because of the challenging economic times but also the mass deportations that occurred in the city. According to Sanchez in 1930, President Hoover denounced Mexicans as one of the causes of the economic depression as ‘they took jobs away from American citizens’ -and so he initiated plans to deport them” (Sánchez 213). In action, this looked like immigration raids in public spaces, like Placita Olvera not far from here, or government officials going door to door offering families and individuals a “choice” between train tickets back to Mexico - regardless of citizenship status – or the option stay and lose access to government assistance. Sanchez notes that by 1931 half of the Mexican population in Los Angeles was unemployed and that by the end of 1934 over 13,000 Mexican residents and Mexican American citizens were sent to Mexico.

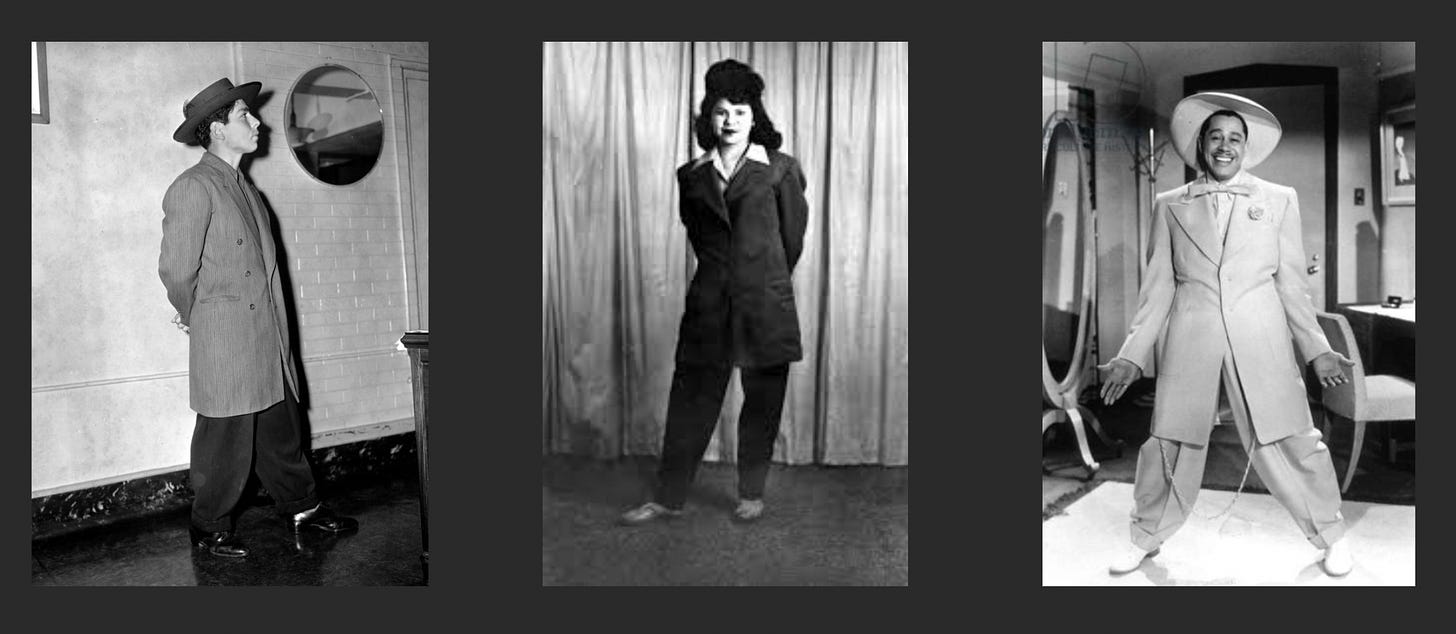

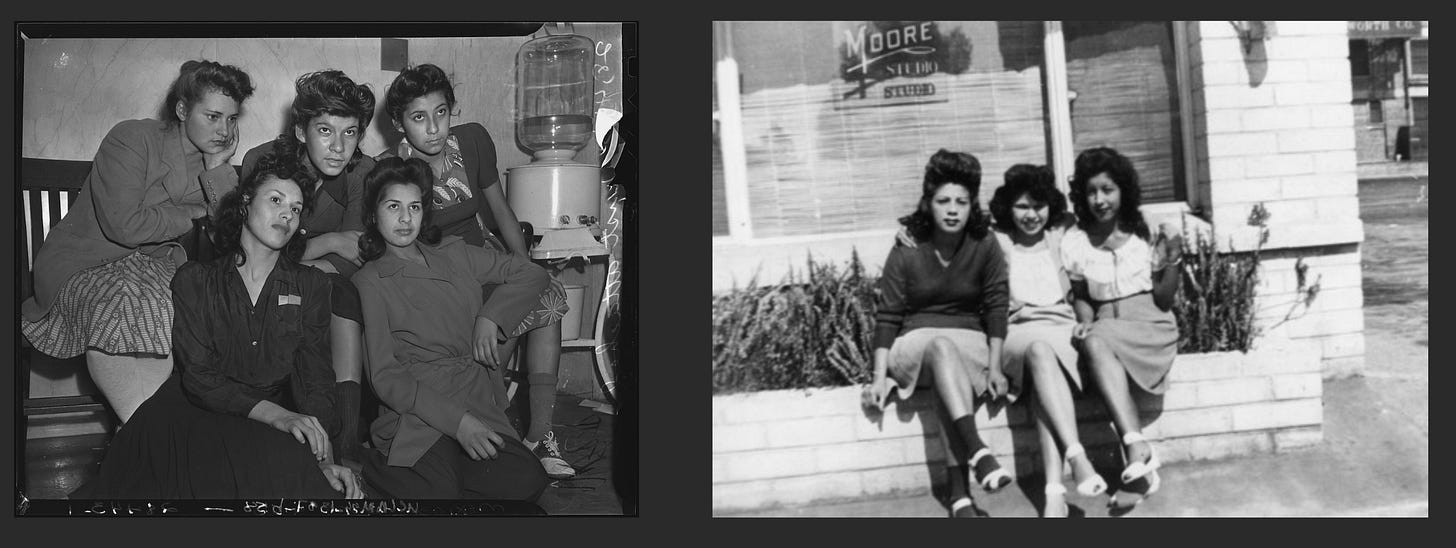

During the war years, opportunities to work were incredibly valuable to Mexican American youth who could suddenly earn meaningful wages and thus have more disposable income to go towards leisure, entertainment, and of course, clothes. As historian Catherine Ramírez observes in her book The Woman in the Zoot Suit: “for many young women and men who came of age in the early 1940s, the zoot suit and its accessories were signs of affluence… allowing a generation that had been forced to wear ‘welfare clothes’ during the Great Depression to take pleasure in appearance” (Ramírez 59). The zoot suit, which originated with Black youth on the East Coast in the jive and jazz scene, included large billowing pants that taper at the ankle and a long fingertip coat, which were worn by both men and women (Ramírez 4, 88). Women who wore the suit might opt to wear a knee length skirt – dangerously short at the time – in addition to the coat, with hair teased into beehive shapes and excessive makeup. Within a Mexican-American context, the Zoot Suit became a symbol of youth subculture that signified earned wealth and social mobility. While Pachucas and Pachucos might have been admired by their peers for their “buenas garras” (“cool threads”) and “spirit of adventure,” they were widely criticized by other Mexicans and whites, who read their style of dress and indulgence in leisure as excessive and unproductive.

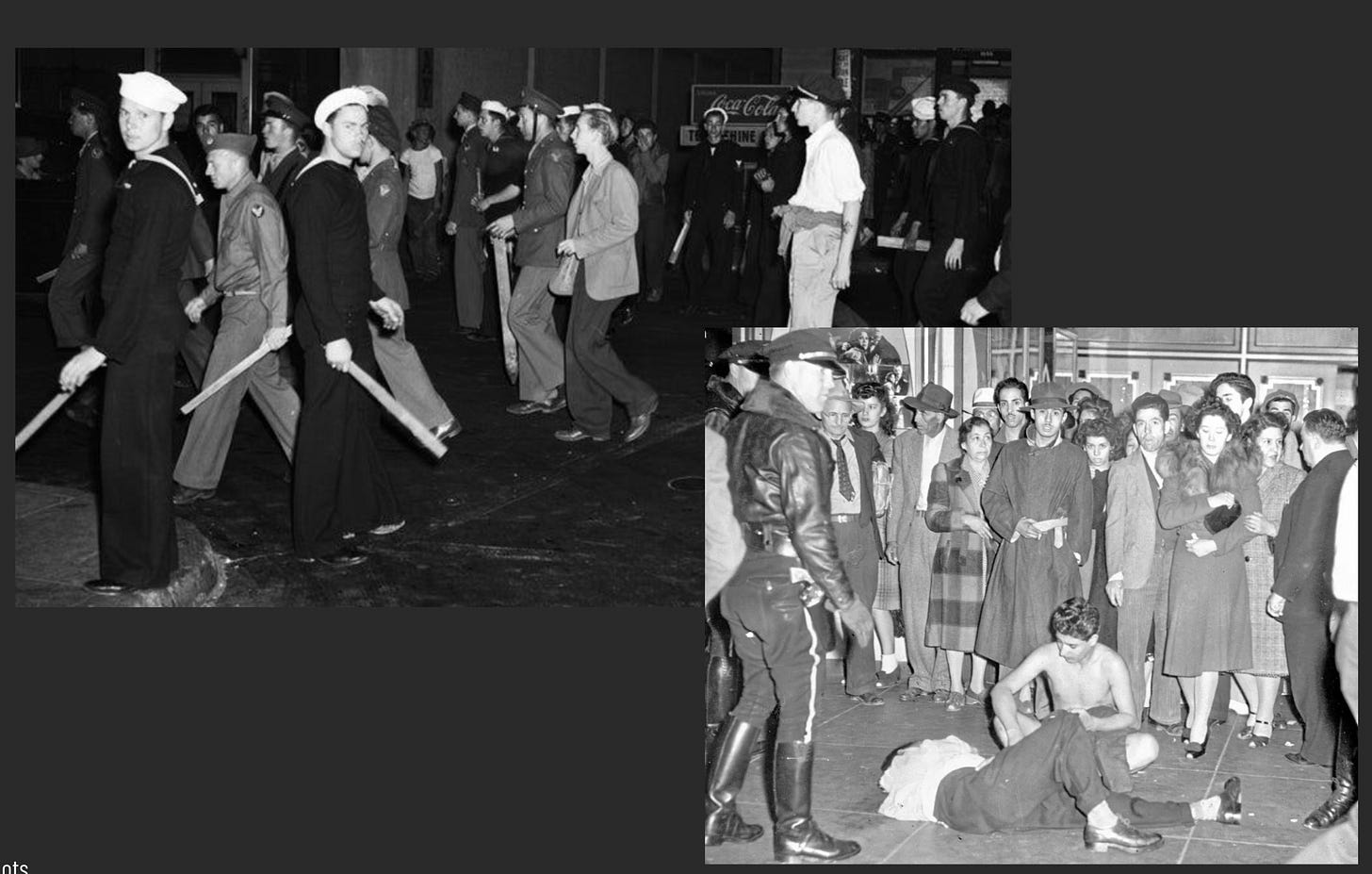

At the time, Los Angeles as a city was “a homefront environment that highly promoted leisure as a patriotic duty” for servicemen on leave or stationed at the various training and naval bases in Los Angeles County (Escobedo 8). However, the “patriotic duty” of those not directly serving in the war was to work. Youth of color who hung out on street corners or spent time downtown at dance halls and movie theaters were put under new forms of scrutiny and marginalization because of their racialized otherness – emphasized through their clothing – which was now on display in new social contexts. Due to rations on fabric at the time, donning the zoot suits, which used excessive fabric to create long, dramatic coats and billowing pants, was read as an affront to both national efforts to prioritize wartime needs and to Mexicans who were seeking to capitalize on the moment and show patriotism and loyalty to the US. Forgetting that youth who wore the zoot suit often had to work long hours in factories in order to afford their clothing and a night of fun, Pachucas and Pachucos were labeled as unproductive delinquents by those outside of the subculture. Tensions toward Pachuco and Pachuca youth escalated, leading to the Zoot Suit Riots which took place in Los Angeles from roughly June 3rd - June 13th in 1943. During this time, mobs of white servicemen attacked Mexican Americans – some zoot suitors and some not – beating them and publicly stripping them of their clothes and even cutting some victims' hair. While this especially violent episode greatly impacted Pachuco men and women, particularly in the media aftermath, the suit remained in vogue, and became a symbol of ethnic pride and political refusal that emphasizes the right to beauty and belonging for Chicano and Latinx folks.

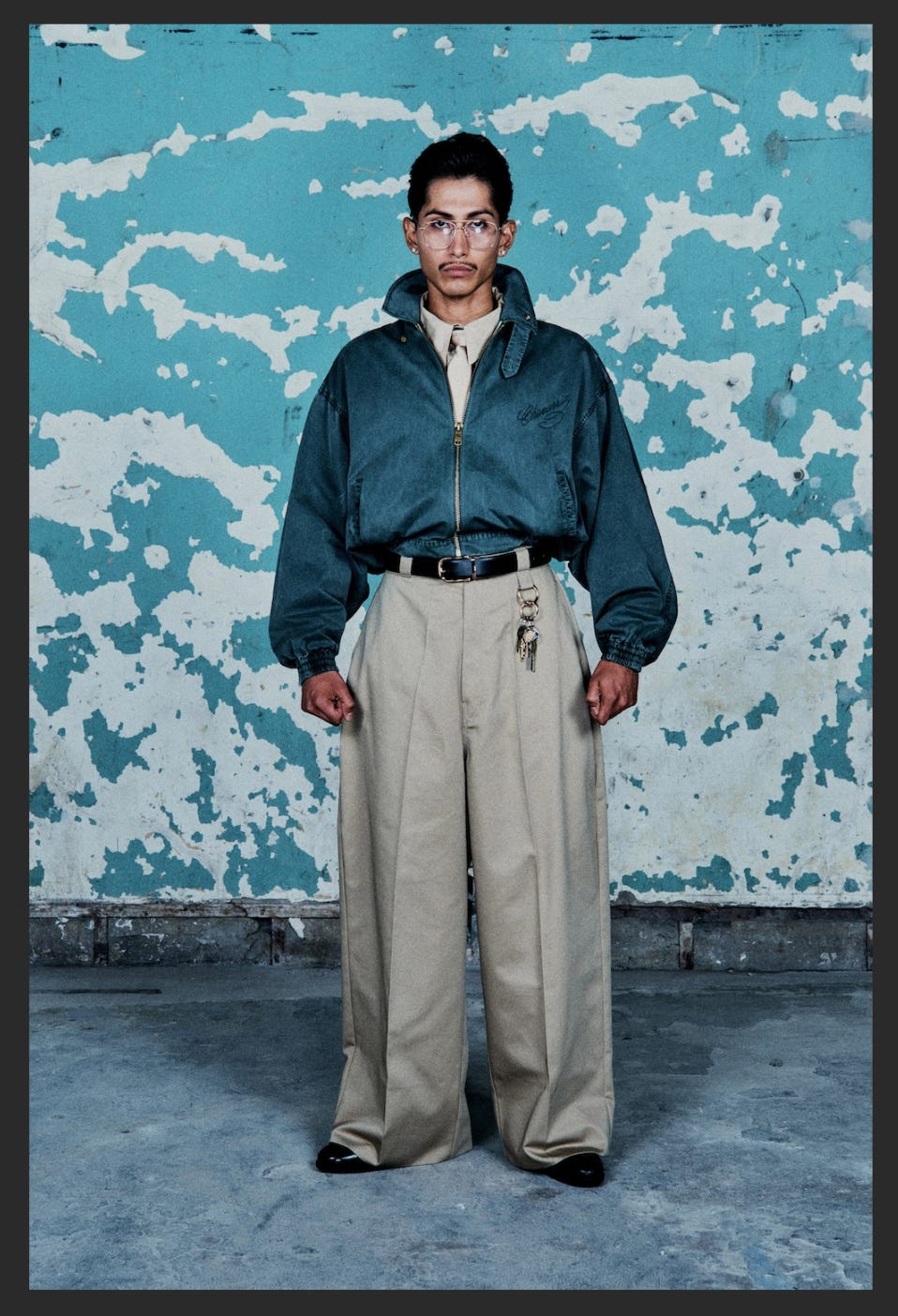

In an interview with Dazed Fashion, Chavarria stated that his inspiration for the collection was “the everyday people on the street, the people who work the jobs that make the country run.” Willy Chavarria has directly stated that his designs draw from Pachuco and Pachuca style as well as the clothing worn by farmworkers, and uniforms typically associated with blue collar jobs. His collection América is predominantly composed of menswear and centers on familiar pieces elevated through precise tailoring.

The first look of the show is made up of a mid crop utility jacket in a washed teal blue. On the left front panel the name “Chavarria” is embroidered in elaborate cursive. The collar of the jacket is popped, framing a crisp khaki colored collar and tie. The model’s shirt and tie perfectly match a pair of wide leg trousers that drape nicely between sharp creases and cascade into a full break at the hem. Dangling from a belt loop are a set of keys. The look emulates the uniform typical perhaps of maintenance or custodial workers, and is reminiscent of Pachuco style, particularly the excess fabric of the pants and in the styling of the models hair into a slick pompadour.

Pairing the familiar workwear styles with the excess of Pachuco aesthetics functions to make visible work that is otherwise and intentionally made invisible. As Chavarria notes, the collection seeks to celebrate the workers whose labor is invaluable but often unrecognized or more accurately overlooked. “Everyday people on the street,” as he calls them, generally blend into the background in the same way workers in plain uniforms do. But by elevating workwear pieces into refined garments, Chavarria affirms the dignity of these workers and the value of their labor. In addition, by subtly alluding to Pachuco aesthetics, Chavarria also invokes their politics of refusal by mobilizing excess as a means of self adornment and gaining visibility. Just as the lyrics in the song “Querida” direct the listener to witness the singer’s pain and suffering, Chavarria’s reimagining of the workers uniform calls for a heightened awareness of the struggle experienced by the person who works and wears those clothes.

As I mentioned previously, young Mexican Americans in the 40s often had to save in order to afford a zoot suit. Owning one became a symbol of pride that demonstrated work ethnic and at the same time suggested an unwillingness to accept social marginalization. Ramirez notes that Pachucas and Pachucos who flaunted their disposable incomes underscored the instability of class and race categories by refusing to stay in their social and/or physical space (61). While I agree with Ramirez on this front, I would add that the suit also destabilized gender categories, which we see in these two designs. In the first, a male model wears a slim fitting long jacket with rounded shoulder pads. Beneath, is a black shirt and tie tucked into a knee length black skirt with a subtle A-line design. The model is also carrying a black leather clutch. In the second look, supermodel Paloma Elsesser wears a tight white tank top tucked into dark high waisted trousers. They have a similar silhouette to the pants in the first look and are accessorized with the same set of keys.

While generally, Pachuca women wore both the skirt and pant version of the suit, both options carried with them different gendered and sexed connotations. If it wasn’t actual skin that was exposed by a shorter skirt, then it was the all too curvaceous silhouette the clothing accentuated that was appalling to both traditional Mexican and American sensibilities. The aesthetic excess of the Pachuca is not necessarily located in her clothing but rather in the assumption of hypersexuality as a woman who dresses in hyper-feminine style for her own embodied and aesthetic pleasure and occupies public space away from the protection and watchful eye of parents at home. For women who wore the men’s version of the suit – the long fingertip coat and billowing pants – they achieved a different kind of aesthetic excess through more masculine performances of race and gender. The pant version of the suit gave women a noticeably more masculine silhouette, upsetting gender presentation rules, and expectations by transgressing across the gender binary. Thus, by wearing the garments of her male, gang-oriented counterpart, the Pachuca in the zoot suit moved herself in closer proximity to criminality and violence. These false assumptions lead outside members to fear the woman in the zoot suit who not only dressed like a man but acted like one too. But what do we make of the man who dresses and acts like a woman?

To answer this, I’d like to turn back to the Zoot Suit Riots, where Mexican men and zoot suitors were publicly stripped of their clothing. Scholar Mauricio Mazón suggests that this violence sought to symbolically castrate Mexican men whose investment in style and personal adornment had already marked them as feminine. By publicly humiliating and de-sexualizikng these men of color, white men were able to affirm their superiority and power within a broader social and sexual landscape. Ramírez notes that sex and sexuality were certainly important factors in the riots as some newspapers at the time claimed the brawl started after a gang of Pachucos had abducted two white women and sexually assaulted them. However, Ramirez tells us that other newspapers suggested that the violence erupted because white men were frustrated that they did not have sexual access to Mexican American women, and at least one paper suggested it was because white men were fed up with “loose girls of the Los Angeles Mexican quarter” who took advantage of unsuspecting sailors with pockets full of money. And so because there are a few different possibilities of who was denied sex, who had weaponized sex, and who had an appetite for sex – I think it’s likely that sex was not the only thing considered when deciding to rip the clothes off these young men’s bodies. I read this violent act as an attempt to strip the humanity of these men by destroying what had become a symbol of pride and source of embodied pleasure. I imagine the suit allowed these men to cultivate a relationship with their bodies and sense of self that was not oriented around productivity or capacity but rather quite simply the gratification of wearing something you like. Put differently, I think the suit allowed these men to understand themselves as beautiful and made the desire to be seen safe enough to explore. In her writing on Black Dandyism professor of Africana studies Monica Miller theorizes that the space between skin and uniform is what transforms the body from a cliché to an interrogation (Miller 245). These white sailors sought to reinscribe the cliché notions that Mexicans are ugly, other, and only good for work by taking away the clothing that invited and allowed both men and women to explore their bodies in non-productive pleasure focused ways.

Ramirez writes that following the riots the male Zoot Suitors would be pathologized as “queer” and “sexually perverse” precisely because their desire to look and feel good was seen as feminine. Chavarria is an openly gay designer who has centered queer aesthetics and issues in his work. Keeping in mind the way the Zoot Suit queers its wearer and Chavarria’s own investments in queer liberation, it becomes easy to see how these designs seek to reopen the space to explore gender and sexuality through style and the feelings of pleasure dressing offers us.

By way of conclusion, I’d like to return to the metaphor of the echo. It’s fairly well known and accepted that styles and trends cyclically come in and out of fashion. Although Chavarria’s status as a premier fashion designer puts a brighter spotlight on Pachuco styles, it’s also true that the zoot suit has remained – to a certain extent – popular and visible since the 1940s.

Growing up in East Los Angeles, I have always seen zoot suits in the windows of shops along Whittier blvd, or being worn by folks at car cruises or special family occasions. At my highschool, there was a set of kids who all wore vintage style clothes every single day trying to emulate this look. And I think I will go to my grave with the memory of one of my first clubbing experiences where the crowd at the Avalon of Hollywood parted to make way for a couple dressed in zoot suits so they could have room to swing and jive to Pitbull. I bring this all up to say that the zoot suit in one way or the other has remained a constant. It’s not like other trends that come and go, it’s like an echo that has managed to sustain itself even after the original sound has stopped. My hope is that my presentation today has demonstrated how Willy Chavarria’s collection América has sought to add to that echo by embracing the styles, aesthetics, and political goals set forth by the Pachuca and Pachuco youth of the 1940s. Like them, Chavarria has turned to fashion as a valuable site to negotiate belonging in the United States and interrogate the way work and desire impacts our lived experience of race, gender, and class.